Post by jshuey on Nov 11, 2014 6:14:01 GMT -8

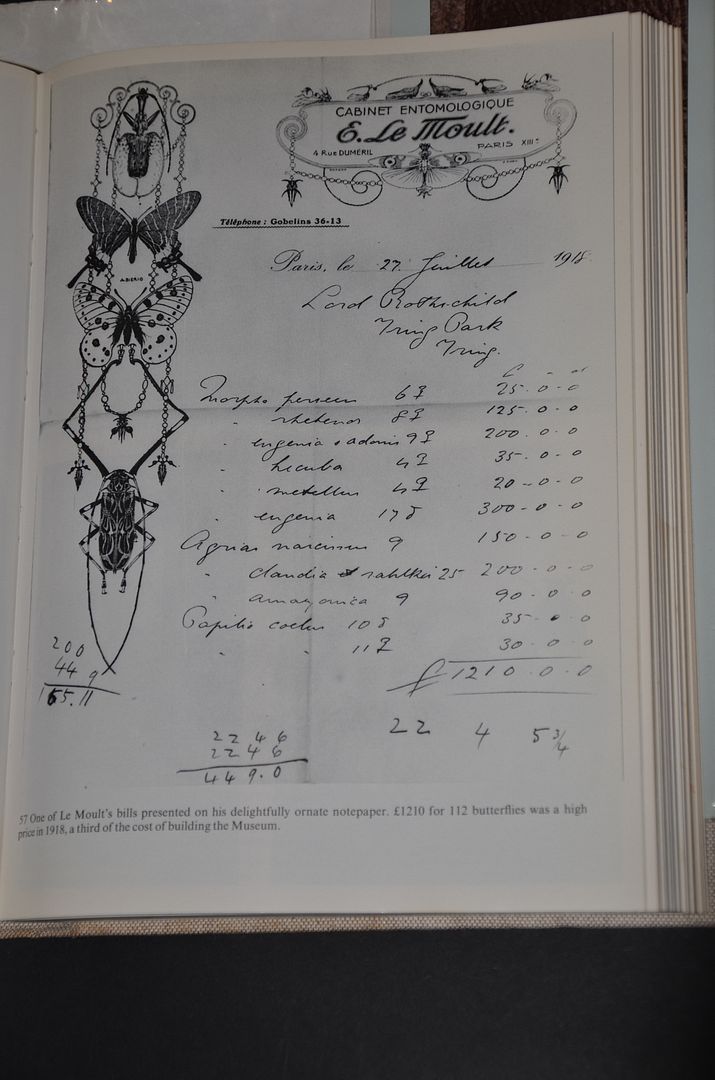

So, first you have to acknowledge that Chuck is funny – but accurate. Take a look at this link - butterfliesofamerica.com/L/t/Prepona_laertes_a.htm - and you will see type specimens of the many species and subspecies names applied by Fruhstorfer and Le Moult to Prepona laertes. I can forgive Fruhstorfer a bit (his names at least look different) – but Le Moult was after money – pure and simple. I will admit, that variation in some populations would lead you to think that two entities are involved – and for several years I thought that Prepona laertes octavia in Belize was two species. Now that I’ve seen around a hundred or so specimens – there is no doubt in my mind that I was wrong about that. Le Moult was especially inclined to describe more than two new subspecies from the same site – based on one specimen each.

So, back to the topic – in my mind, species and subspecies are “concepts”. In theory, species are real – and represent probably the only “real taxonomic category” in taxonomy. Things get even messier when you start talking about “what is a genus”. I think that fewer and fewer taxonomists use the old “biological species” concept. The reality is that most use a “morpho-species concept” – if it looks different, then it is different.

Many people are moving towards a phylogenetic species concept – that if two lineages are well along separate evolutionary paths, then they are different evolutionary lineages (aka species). (Don’t ask me to define “well along” though). Under this definition, all the island subspecies of Anaea troglodyte in the Caribbean would be raised to full species. Each island supports a population that is well down a unique evolutionary path, so much so that the bugs look quite different. If you tried, you could probably interbreed these lineages – but that is irrelevant – they are on different paths, trapped in different islands, and that evolutionary history should be recognized. And such species don’t have to look very different to fit this definition, and bar-coding is turning up many examples of “new species” that no one can easily recognize (but that doesn’t impinge on the reality that they are real and different species). On the otherhand, clinal subspecies such as Limenitis archippus with subspecies such as archippus, floridensis and watsoni do not fit this definition. These populations intergrade and breed with each other – and despite their “morpho-differences” are clearly the same evolutionary entity. This is a wide spread species that, thanks to evolutionary pressures in different regions, has moved towards very different looking phenotypes that are maintained by local selection pressures.

The bottom line is that when honest people throw out new names – they are doing so as their best guess – a hypothesis – that future taxonomists can test. For example – I have found up to three “Le Moult subspecies” in single traps in Belize. Most of his subspecies and species concepts do not stand up well if you actually take a look at them – and in this case – you don’t even have to look very hard. Good taxonomists are trying to find real answers that will stand the test of time. When I was a student – I threw out a name Euphyes bayensis that I knew many people would not believe - lepidopteraresearchfoundation.org/journals/27/PDF27/27-160.pdf – and indeed many people immediately rejected this species concept. But as people gained experience with these populations, they saw what I saw, and the species is now an accepted name. Not that I’m that great of a taxonomist – but that’s the goal. You set out a hypothesis that others can test.

So - my point here is that it is all very murky,

John

So, back to the topic – in my mind, species and subspecies are “concepts”. In theory, species are real – and represent probably the only “real taxonomic category” in taxonomy. Things get even messier when you start talking about “what is a genus”. I think that fewer and fewer taxonomists use the old “biological species” concept. The reality is that most use a “morpho-species concept” – if it looks different, then it is different.

Many people are moving towards a phylogenetic species concept – that if two lineages are well along separate evolutionary paths, then they are different evolutionary lineages (aka species). (Don’t ask me to define “well along” though). Under this definition, all the island subspecies of Anaea troglodyte in the Caribbean would be raised to full species. Each island supports a population that is well down a unique evolutionary path, so much so that the bugs look quite different. If you tried, you could probably interbreed these lineages – but that is irrelevant – they are on different paths, trapped in different islands, and that evolutionary history should be recognized. And such species don’t have to look very different to fit this definition, and bar-coding is turning up many examples of “new species” that no one can easily recognize (but that doesn’t impinge on the reality that they are real and different species). On the otherhand, clinal subspecies such as Limenitis archippus with subspecies such as archippus, floridensis and watsoni do not fit this definition. These populations intergrade and breed with each other – and despite their “morpho-differences” are clearly the same evolutionary entity. This is a wide spread species that, thanks to evolutionary pressures in different regions, has moved towards very different looking phenotypes that are maintained by local selection pressures.

The bottom line is that when honest people throw out new names – they are doing so as their best guess – a hypothesis – that future taxonomists can test. For example – I have found up to three “Le Moult subspecies” in single traps in Belize. Most of his subspecies and species concepts do not stand up well if you actually take a look at them – and in this case – you don’t even have to look very hard. Good taxonomists are trying to find real answers that will stand the test of time. When I was a student – I threw out a name Euphyes bayensis that I knew many people would not believe - lepidopteraresearchfoundation.org/journals/27/PDF27/27-160.pdf – and indeed many people immediately rejected this species concept. But as people gained experience with these populations, they saw what I saw, and the species is now an accepted name. Not that I’m that great of a taxonomist – but that’s the goal. You set out a hypothesis that others can test.

So - my point here is that it is all very murky,

John