|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 6, 2014 1:47:15 GMT -8

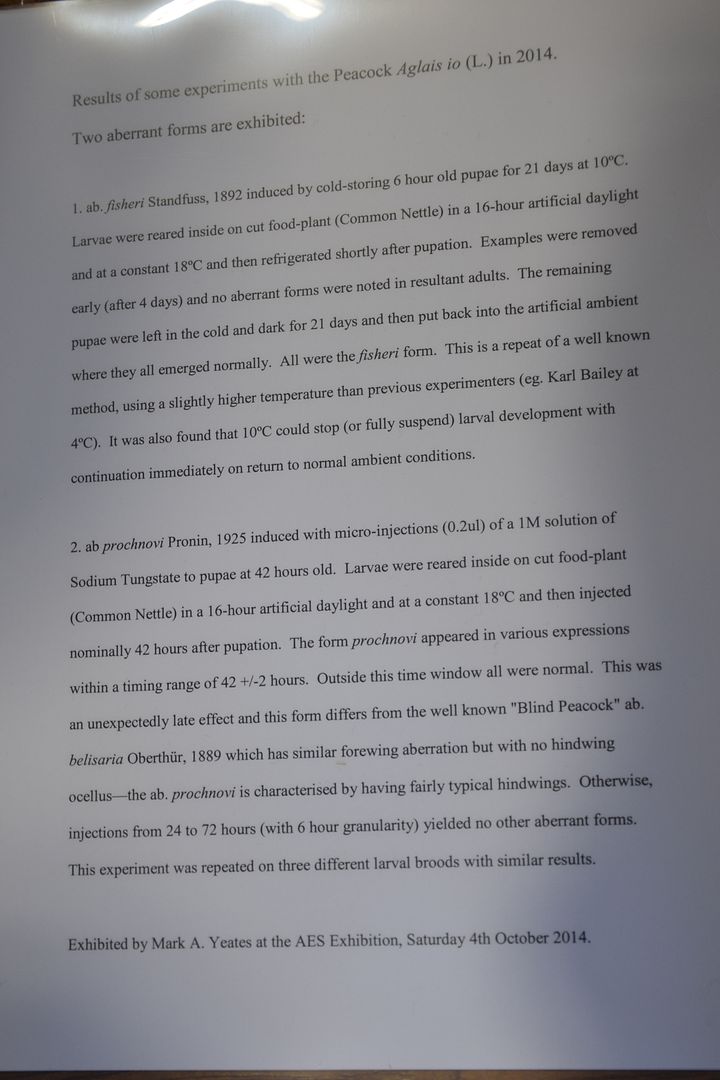

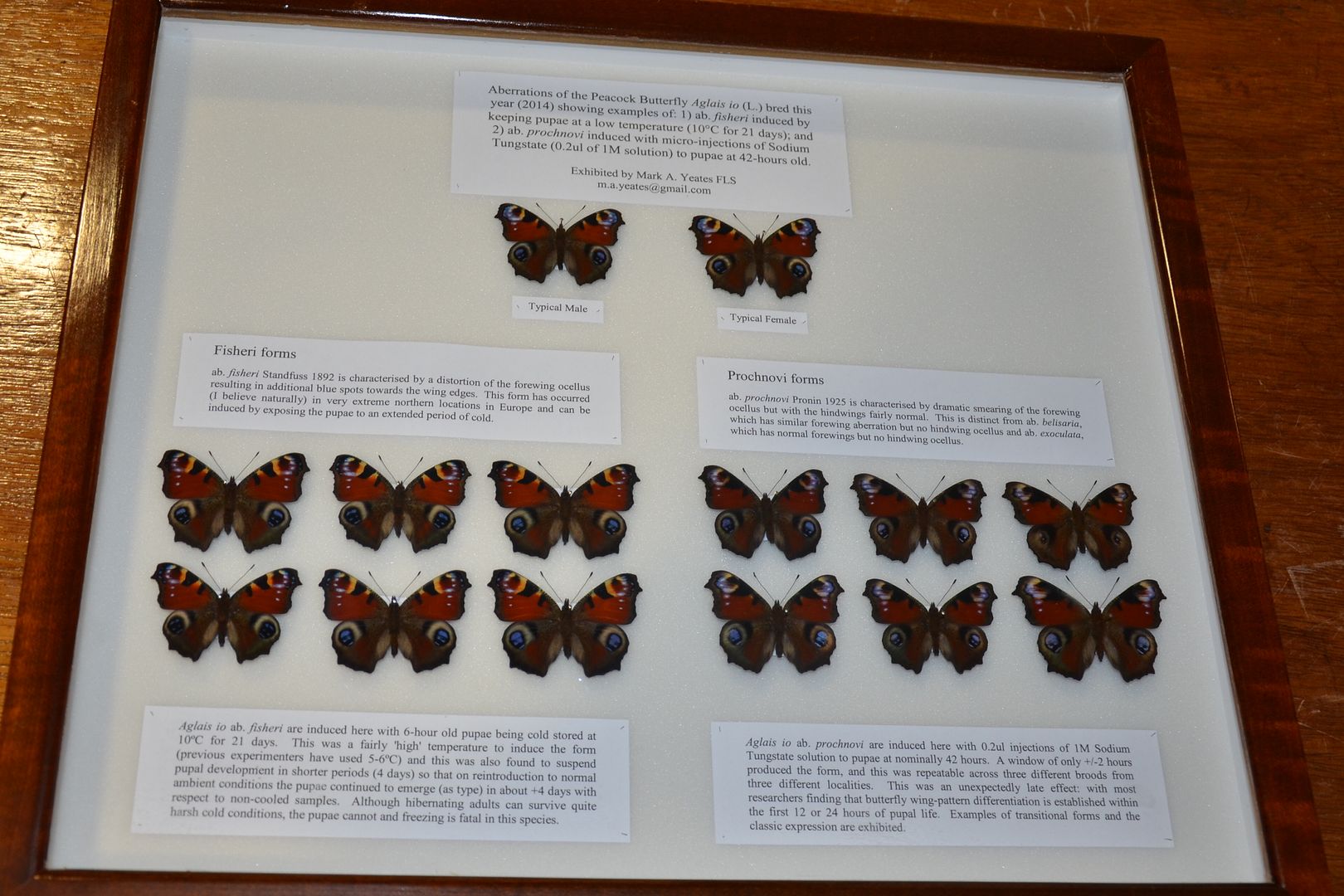

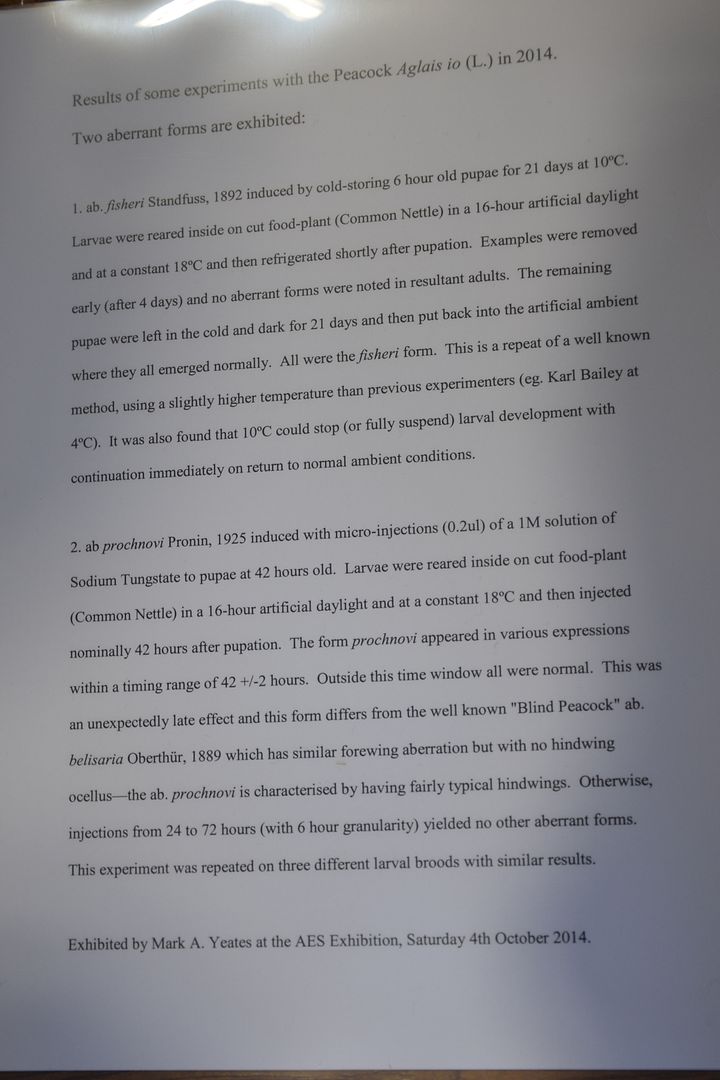

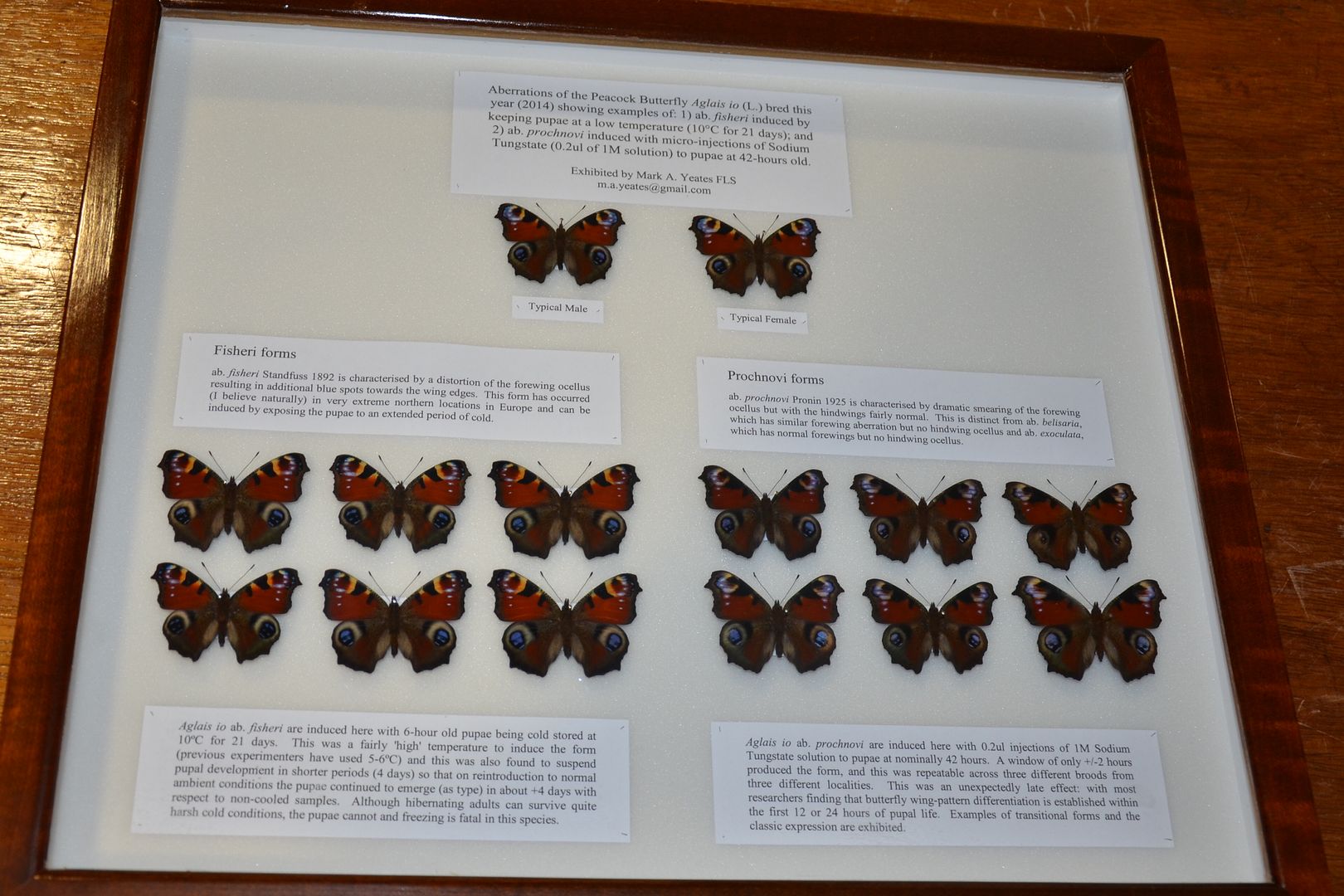

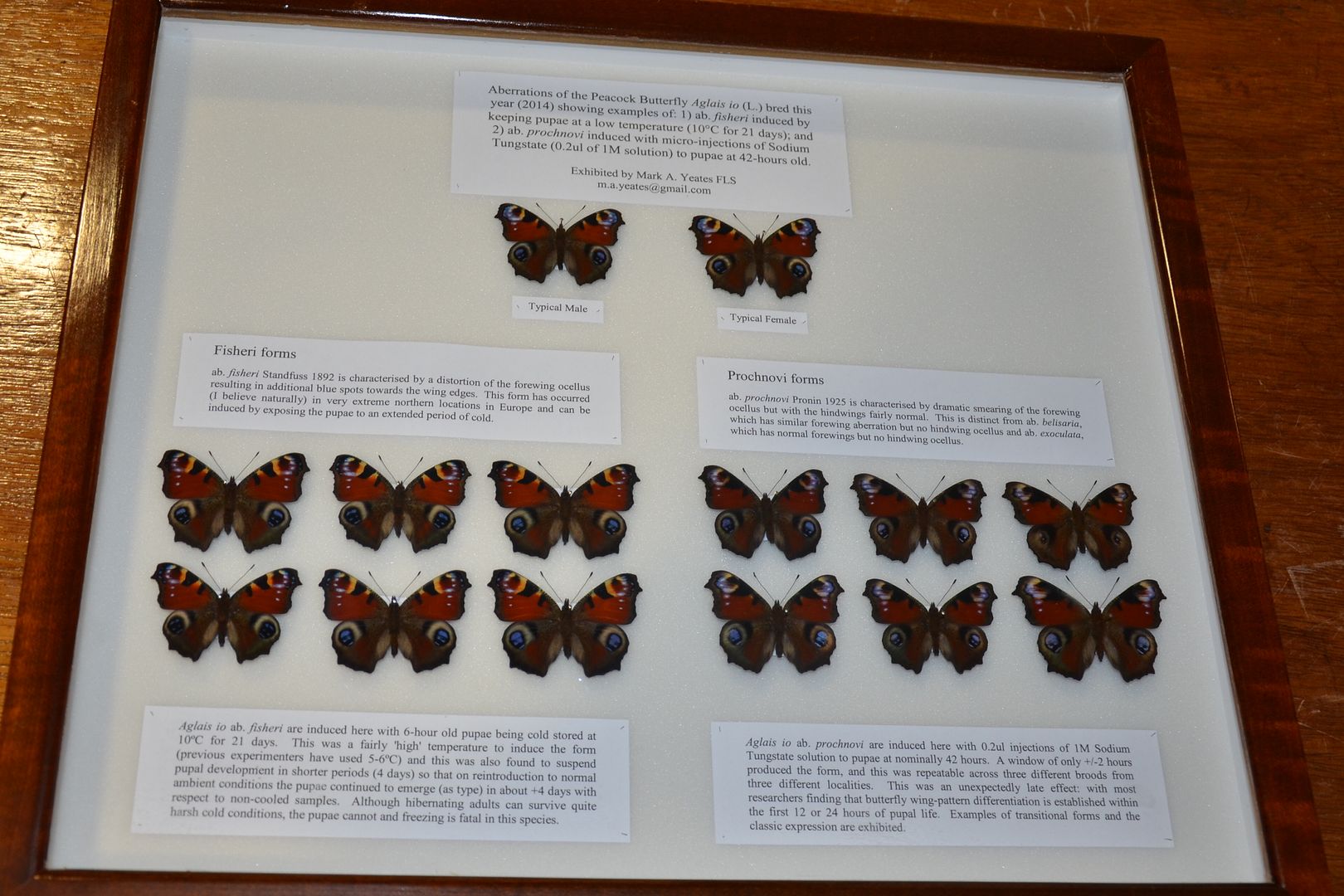

Recently, I have noticed many Nymphalidae and a few European Lycaenidae experimental aberrations for sale. There seems to be two ways of achieving these often spectacular looking butterflies. This is either by pupae cold shock treatment or by chemical injection. The latter method has produced some remarkable melanic variation. I have noticed that these methods do not produce the lighter genetic aberrations that occur in the wild. Interestingly at the recent A.E.S fair in the U.K, there was a box in their Annual exhibition where two of the Inachis io aberrations that have occurred in the wild were reproduced by experiments. One of these aberrations has been reproduced by selective cold temperature treatment and the other by chemical injection.. This study by Mark Yeates has shown us that although many aberrations are genetic, others that have naturally occurred in the wild are due to the pupae being subject to colder temperatures. One collector has mentioned aberrations have been produced by a higher temperature, although I have seen no specimens as yet, that have been obtained by using this method. Many aberrations are very rare in the wild and have been much sought after by collectors. Many famous British aberrations or forms as Museum staff now call them, have appeared in many of the famous 19th lepidoptera works of that country . Certain of these early 19th century aberrations were often unique specimens, that have been included in the works of successive authors. Early historic aberrations were considered great rarites and were all wild caught or bred from wild collected larvae. Later, selective breeding by well known lepidopterists produced a remarkable range of aberrations, usually in certain moth species, especially those of the Actiidae family. Eventually the strains of these much sought after aberrations died out through the weakening of the breeding stock. Some of these varieties have never been reproduced. I believe as E.B.Ford has shown in his work on genetics, that the study of aberrations has had much scientific value . Chemical injection is now being used with other butterfly families. Recently, the skill of those lepidopterists involved in these experiments, have produced some spectacular Papilio machaon European subspecies varieties. I do think the prices for these man made aberrations will stay fairly low if the market is flooded. I expect out of the many pupae that are subject to chemical or cold shock treatment only a fraction survive unless this technique has been worked out to a fine art. I would have liked to have shown some of the other aberrations being produced by European lepidopterists, but do not yet have their permission. Your views on artificially produced experimental aberrations please. Below a case in the AES exhibition showing two experiments with inachis io that have produced naturally occurring named aberrations.   A case of experimental aberrations for sale at the A.E.S. Most of the specimens in this box do not attain the standard of many of the others I have seen recently.  A case of bred and what looks like experimental aberrations. A much better quality box   |

|

|

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 6, 2014 4:28:22 GMT -8

The best of these remarkable experimental aberrations are being produced by the Slovakian Entomologist Ladislav Misko. Some of you may have seen these at Ladislav's table at Juvisy. They are simply stunning  A few are shown here with Ladislav's kind permission.  Melitaea phobe.  Issoria lathonia.  Melitaea trivia  Papilio machaon  Lycaena phlaeas  Araschnia levena.  Polygonia c-album. |

|

|

|

Post by boghaunter1 on Oct 6, 2014 13:54:37 GMT -8

Hello again, Following are 7 wild examples of aberrations of the Mourning Cloak ( Nymphalis antiopa) that I collected here in N.E. SK, Canada; 1 & 2 were collected in Aug. 2007 & were shown before on this forum. Numbers 3 - 7 were collected in Aug. 2012 & this is the 1st time I have shown them here. As stated in the discussion genuine "wild" examples are exceedingly rare in nature & unbelieveably all 7 specimens were collected along the same 7 mile stretch of back rd. (basking on damp road) near the Manitoba border. I have never observed or collected similar specimens anywhere else. Interestingly, regarding the cold vs. hot shocking, all of these specimens (except no. 2) were collected after prolonged hot spells of +30 to +34C, 10-14 days prior to their collection. Specimen no. 2 was the only one collected 10-14 days following a sudden cold snap (down to -3 C for a number of nights). I am only aware of one other similar wild specimen collected by another collector approximately 100 mi. further N., right along the SK/Man. border a number of yrs. ago. That specimen was collected in the spring time as a winter hibernator that was found in a wood pile. I am not aware of any similar specimens collected in SK. I contacted the National Collection in Ottawa & they have a series, all bred, from California. I have been in contact with Dr. Arthur Shapiro, from the U. of C. at Davis, California about these particular aberrations... he wrote a number of interesting papers on them & of how he produced them by cold shocking. Interestingly he was only able to produce these same type of aberrations fairly easily by cold shocking pupae from S. California & other S. states. He had no luck with the same technique on more northern populations (Alaska). He surmised that more northerly populations were, through time, exposed to much harsher conditions (than southern populations) making them more genetically resistant to weather shocks & therefore wild aberrations in northern populations were very rare. Specimens 3-7 were collected on 2 consecutive days in mid Aug... I was hopping about in disbelief & excitement as most of them were freshly emerged & showed a whole range of natural aberrations. Specimen no. 7, with the missing blue spots, is a fairly common ab./var. found regularily in many areas whenever populations are abundant.        John K. |

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 7, 2014 10:07:16 GMT -8

John

Very interesting information on Nymphalis antiopa aberrations. It is well known that these types of aberrants are excessively rare in the wild. Some collectors would be lucky to encounter one such extreme aberration in their lifetime. So two and then several in the same locality is amazing. The first captures must have been sensational, but the second must have seemed extraordinary. I think I might have pinched myself to see if I was dreaming. So congratulations on your super finds.

Although some collectors may not collect aberrations, many do. They have produced some of the highest prices that were ever paid for butterflies. One, the all green Ornithoptera borchi springs to mind and the golden eurphorion seems to be gaining a high price at a remarkable speed. The first seems to have been a wild capture, the second was produced by selective breeding.

It would be interesting to hear any views? on experimental aberrations. It would also be most welcome to hear other collectors stories of exciting finds of rare aberrants in the wild. I expect those that are self caught may be treasured indeed. They are so rarely found.

|

|

|

|

Post by irisscientist on Oct 7, 2014 14:40:11 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 7, 2014 20:54:32 GMT -8

Thank you for the link -all very interesting, I noticed this discussion was about cold shock treatment, many including those above, were also now being produced by chemical injection, which especially produce dark to melanic varities. Temperature experiments, I believe go way back to the turn of the century.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Post by irisscientist on Oct 7, 2014 22:56:11 GMT -8

I quote this section of the original thread which also comments on chemically induced aberrations: |

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 8, 2014 9:27:27 GMT -8

Thanks again Mark for your input. I read the link you provided too quickly over breakfast early this morning before work, I guess I was still half asleep. P.S =I had no luck with those links that were included in the original thread? They now seem unobtainable.

Peter.

|

|

|

|

Post by irisscientist on Oct 8, 2014 10:01:55 GMT -8

|

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 8, 2014 11:55:56 GMT -8

Thank you Mark for the further links to those interesting papers, I shall enjoy reading them.

Peter.

|

|

|

|

Post by nomad on Oct 9, 2014 9:35:12 GMT -8

One of the best modern day and easy to read accounts of how aberrations arise can be found in the book by A.S Harmer , which is beautifully illustrated by A.D.A. Russwurm ' Variation in British Butterflies ( 2000) Chapter four ' Butterfly Genetic's in Theory', pages 53-84 . Harmer mentions in his first paragraph in this Chapter " Throughout the greater part of our long, rich collecting heritage spanning some three centuries or more, aberrations have attracted the curiosity and attention of British collectors. Our relative paucity of species, when compared to the numbers enjoyed by European lepopterists, has been an instrumental factor in the huge interest and study of these unusual forms have received in the past and continue to receive. Continental collectors have long regarded Britain as being exceptionally favoured with respect to the apparent abundance of aberrations. Possibly, the British Isles isolated geographically as they are, with a changeable climate, provide conditions more conductive to producing forms than on mainland Europe. Whatever the reasons may be, we are indeed extremely fortunate. " Some localities in the U.K seem to produce many outstanding aberrations in certain years, and point to a simple recessive gene. The cold winters that have been followed by very hot years in Britain have also produced many extreme environmental aberrations such as melanic fritillaries. Harmer tells us that aberrations produced artificial means have been known for over a century and cites Standfuss 1901-1902. I have found out that Prof Dr Max Standfuss ( 1854-1917), a Swiss biologist, wrote a paper which appeared in the ' Entomologist Journal ' : Synopsis of experiments in hybridization and temperature made with lepidoptera up to the end of 1898. Standfuss it seems wrongly attributed his results to ' Lamarchian inheritance'. Larmarckism is an idea that an organism such as a butterfly can pass on characteristics that it had acquired in its lifetime to its offspring : soft inheritance. The English entomologist - Frederick Merrifield ( 1831-1924) wrote a paper that was published in the transactions of the Entomological Society of London for 1890 entitled ' Systematic temperature experiments on some lepidoptera in all their stages ' More recently, following in the footsteps of these early pioneers. Karl Bailey, the U.K lepidopterist has had much success with Nymphalidae in obtaining many outstanding aberrations with temperatures as low as minus 8 C to over 40 C. Are these experimental aberrations just pretty and unusual curiosities or do they have scientific value. Harmer mentions that collectors - may have strong views regarding temperature experimentation? Harmer mentions there may be several benefits from them, such as it reveals the " spectrum of gradation in the development ( often following a sequential progression or morphocline) That sometimes exists between what may at first to appear to be quite separate and distinct aberrational forms." Alex Harmer has bred and caught many outstanding aberrations. One of my favourites are those of a long series that he bred of the Ringlet- Aphantopus hyperantus ab lanceolate from a single wild caught female. An example of a simple recessive gene aberration. A few of these beautiful aberrations where the eye black circles are replaced by tear drops, could be bought at the recent A.E.S. fair in London . By the time that I arrived all of the pure ab lanceolate specimens had been sold. Below are two of Harmer's intermediate aberrations of the Ringlet.  |

|